Summers have gotten wetter for the UK thanks to the warm phase of the AMO (Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation) but when this warm phase peaks in a year when El Nino is coming on, expect record rains in the UK. Both 2007 and 2012 saw a very warm AMO and warm North Atlantic as well as an El Nino coming on which led to a record wet summer. Summer 2007 was the UK’s wettest only to be beaten by 2012. This afternoon I want to look at the soggy summer of 2007.

Warmer Atlantic Ocean blamed for UK’s gloomy summers

8 October 2012, by Tamera Jones

The UK’s recent run of dismal summers were strongly influenced by a major warming of water in the North Atlantic Ocean which started back in the 1990s and continues today, say scientists.

Wind and rain.

Wind and rain.

They add that while the North Atlantic remains as warm as it is, the country is unlikely to see an end to wet summers.

‘You’re not always going to get one, but as long as the Atlantic is warm, the chances of a wet summer are increased,’ says Professor Rowan Sutton director of Climate Research in the Natural Environment Research Council’s (NERC) National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS), who led the study.

Last time the Atlantic was as warm as it is now, it persisted for nearly 30 years, from 1931 until 1960. This led to a run of wet summers over the UK. Lynmouth in Devon experienced disastrous flooding in August 1952, and severe flooding during August 1948 closed the east coast mainline for three months.

‘The state of the oceans tells you about weather patterns that are likely to evolve several years ahead.’

Professor Rowan Sutton, Natural Environment Research Council’s National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS)

The warm period the North Atlantic is experiencing right now only started around 1996, which suggests it might be some time before the ocean cools down again and we see a return to more agreeable summers. But, as with all things weather related, how long the current warm period will last isn’t easy to predict.

‘We can’t assume that the current warming will be the same length as the previous one. We just don’t know how long it’ll go on for,’ says Sutton.

He and his colleague, Dr Buwen Dong – also from NCAS – describe in a study published in Nature Geoscience how they analysed long-term records of air temperature, rainfall and pressure at sea level for these two warm periods. They compared these records with those from a cool period in between.

By comparing the observed changes with computer simulations of the climate system, they found compelling evidence that the temperature of the Atlantic Ocean influences the whole of Europe’s climate.

‘The state of the oceans tells you about weather patterns that are likely to evolve several years ahead,’ says Sutton.

In particular, they found that a warming of the North Atlantic in the 1990s coincided with a shift to wetter summers in the UK and northern Europe. At the same time, the Mediterranean experienced a shift to hotter and drier summers than usual.

The patterns the researchers unearthed match those experienced in the UK this year, when the country recorded its wettest summer in 100 years. In contrast, countries in the Mediterranean suffered under temperatures of 40 degrees centigrade or higher.

‘We saw a rapid switch to a warmer North Atlantic in the 1990s and we think this is increasing the chances of wet summers over the UK and hot, dry summers around the Mediterranean – a situation that is likely to persist for as long as the North Atlantic remains in a warm phase,’ says Sutton.

Scientists know that the temperature of the North Atlantic swings slowly between warm and cool conditions, which can each last for decades at a time. Not just that, but previous studies have linked sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic with changes in Europe’s climate. But exactly how the two are linked was, until now, unclear.

Now, the pair’s findings suggest that changes in ocean temperature affect the atmosphere directly above, ultimately causing a trough of low pressure over western Europe during the summer, which, ‘steers rain-bearing weather systems slap-bang into the UK’.

‘We know the jet stream is involved in this: there’s a close relation between it and the path weather systems take,’ Sutton says. ‘When the North Atlantic is cool, rain-bearing weather tends to meander northwards over Iceland. But when it’s warm, they tend to slam into the UK.’

The next obvious area of research suggests Sutton is to figure out how long the current warm state could last.

Rowan T. Sutton and Buwen Dong, Atlantic Ocean influence on a shift in European climate in the 1990s, Nature Geoscience vol 5 no. 10, published 7 October 2012, doi

From Met Office

Flooding — Summer 2007

Torrential downpours in May, June and July 2007 left large swathes of the country under water as the rain was followed by widespread flooding. By accurately forecasting the weather, the Met Office kept people informed on what they could expect.

Unsettled conditions dominated the Bank Holiday in early May, bringing rain and showers to many parts of the country. For the following Bank Holiday there was heavy rain. After a reasonably dry start to June, extremely heavy and prolonged rain fell on to an already soggy UK, leading to serious floods which threatened lives and caused substantial damage to property. Tragically some people died and thousands more had to spend nights in temporary accommodation or were left without power.

Part of the reason for the heavy rain was the jet stream – a band of strong winds in the upper atmosphere that influence how weather systems that bring rain to the UK will develop. As the jet stream was stronger than normal, depressions near the UK were more intense. Some of these depressions pulled in the very warm and moist air to the south of the UK, generating exceptionally heavy and intense rainfall.

What we did

- We played a vital role throughout the summer, providing highly accurate forecasts and warnings ahead of the heavy rains.

- Before and during the floods we worked with and advised emergency planners across the UK including the police and military rescue teams, the Environment Agency, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency and COBR (the Civil contingencies committee which leads responses to national crises).

- We issued early warnings of the severe weather several days ahead to advise the public on the possible impacts.

- As more heavy rain fell on already flood-hit areas, we kept everyone informed as the downpours deposited well over three times the monthly average rainfall for June in some places.

The results

- While it is not easy to forecast extreme weather, the heavy rain was well forecast, with Met Office forecasters predicting the heavy and prolonged rainfall.

- There is no doubt that things would have been much worse without early warnings from the Met Office.

What happened in June

On Monday 25 June prolonged heavy rainfall resulted in many parts of north and east England being flooded.

Map of risk of disruption in June

Map of risk of disruption in June

| Dates | Actions |

|---|---|

| 17 to 20 June | Localised torrential downpours continued with many Flash warnings issued. |

| 21 June | News Release issued to highlight unseasonable weather. |

| 22 June | Early Warning issued to public, government and emergency services giving three days’ notice of potential disruption. |

| 23 June | Further warnings and update to Early Warning issued for E/NE England. |

| 24 June | Early Warning updated with highest probabilities for disruption in an arc from Yorkshire and Humberside to the Welsh Borders, with rainfall totals of ‘up to 100 mm or so’. |

| 25 June | Flash warnings issued for heavy and persistent rain across the high risk areas during the day. |

Weather conditions

Surface synoptic analysis map, Monday 25 June at 6pm

Surface synoptic analysis map, Monday 25 June at 6pm

Days before the actual flooding, the ground around the worst-hit areas became saturated by very heavy rain. Many sites in Yorkshire received at least a month’s rainfall in 24 hours.

On Monday 25 June a slow-moving area of low pressure brought a prolonged period of heavy rain to northern and central England. Hitting the already saturated north-east, the water had nowhere else to go and, as a result, led to major flooding.

Impacts

- Five people died.

- Surface water flooding in Hull.

- Widespread disruption and damage to more than 7,000 houses and 1,300 businesses in Hull.

- River Don burst its banks, flooding Sheffield and Doncaster.

- Flooding in Derbyshire, Lincolnshire and Worcestershire.

- Highest official rainfall total was 111 mm at Fylingdales (N Yorkshire). Amateur networks recorded similar totals in the Hull area.

- There were fears that the dam wall at the Ulley Reservoir near Rotherham would burst.

A heightened alert state was retained during the week 25-30 June, because of the threat of further rain.

What happened in July

The second event caused localised flash flooding across parts of southern England on the morning of 20 July, and later in the day across the Midlands.

Map of the risk of disruption in July

Map of the risk of disruption in July

| Dates | Actions |

|---|---|

| 16 July | Medium-range computer forecast suggests a vigorous weather system could move toward the UK and engage with relatively warm air over northern France.Met Office Executive Board briefed about the chances of this event. |

| 18 July | Early Warning issued in the morning, central and eastern areas of England at risk of disruption from 60-90 mm of rain. |

| 19 July | Risk areas narrowed to south-west Midlands, Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire. Possible rainfall total increased to 75-100 mm. |

| 20 July | Flash warnings for southern and central England issued before 9 a.m. |

Weather conditions

Surface synoptic analysis map, Friday 20 July at 12 UTC.

Surface synoptic analysis map, Friday 20 July at 12 UTC.

A slow-moving depression centred over south-east England, drawing warm moist air from the continent across the UK. Heavy and slow moving rainfall moved northwards during the day.

Impacts

- Widespread disruption to the motorway and rail networks.

- In the following days the River Severn and tributaries in Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Herefordshire, Shropshire broke banks and flooded surrounding areas.

- River Thames and its tributaries in Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Surrey flooded.

- Flooding in Telford and Wrekin, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Birmingham.

- The highest recorded rainfall total was 157.4 mm in 48 hours at Pershore College (Worcestershire).

The future

- In August, Sir Michael Pitt conducted an independent review of the flooding. The review recognised our forecasts and warnings had been timely and accurate and also praised the performance of our Public Weather Service Advisors.

- A key recommendation of the Pitt review, after the floods of summer 2007, was that the Environment Agency and the Met Office should work together, through a joint Flood Forecasting Centre , to improve the capability to forecast, model and warn against flooding.

- Developments in Met Office capability such as 1.5 km resolution models and probabilistic forecasts will help the UK to be more resilient to severe weather.

Last updated: 11 May 2011

From Wikipedia

2007 United Kingdom floods

Severn flood 2007 Interview with ITN

|

|

| Date | 1 June 2007 – 25 July 2007 |

|---|---|

| Location | (see below) |

| Deaths | 13[1] |

| Property damage | about £6 billion |

A series of destructive floods occurred in parts of the United Kingdom during the summer of 2007. The worst of the flooding occurred across Scotland on 13 June; East Yorkshire and The Midlands on 15 June; Yorkshire, The Midlands, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire and Worcestershire on 25 June; and Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire and South Wales on 28 July 2007.

June was one of the wettest months on record in Britain (see List of weather records). Average rainfall across the country was 5.5 inches (140 mm); more than double the June average. Some areas received a month’s worth of precipitation in 24 hours.[2] It was Britain’s wettest May–July since records began in 1776.[3] July had unusually unsettled weather and above-average rainfall through the month, peaking on 20 July as an active frontal system dumped more than 4.7 inches (120 mm) of rain in southern England.[4]

Civil[5] and military[5][6][7][8][9] authorities described the June and July rescue efforts as the biggest in peacetime Britain. The Environment Agency described the July floods as critical[9] and expected them to exceed the 1947 benchmark.[10]

Contents

[hide]

- 1 Meteorological background

- 2 Affected areas in England

- 2.1 Bedfordshire

- 2.2 Berkshire

- 2.3 Buckinghamshire

- 2.4 Cambridgeshire

- 2.5 County Durham

- 2.6 Cumbria

- 2.7 Derbyshire

- 2.8 Gloucestershire

- 2.9 Greater London

- 2.10 Herefordshire

- 2.11 Lancashire

- 2.12 Lincolnshire

- 2.13 Nottinghamshire

- 2.14 Oxfordshire

- 2.15 Shropshire

- 2.16 Warwickshire

- 2.17 West Midlands

- 2.18 Wiltshire

- 2.19 Worcestershire

- 2.20 East Riding of Yorkshire and Kingston upon Hull

- 2.21 North Yorkshire

- 2.22 South Yorkshire

- 2.23 West Yorkshire

- 3 Affected areas in Northern Ireland

- 4 Affected areas in Scotland

- 5 Affected areas in Wales

- 6 Timeline for June and July floods

- 7 Aftermath

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 External links

Meteorological background[edit]

June 2007 started quietly with an anticyclone to the north of the United Kingdom maintaining a dry, cool easterly flow. From 10 June the high pressure began to break down as an upper trough moved into the area, triggering thunderstorms that caused flooding in Northern Ireland on 12 June.

Later that week, a slow moving area of low pressure from the west of Biscay moved east across the British Isles. At the same time, an associated occluded front moved into Northern England, becoming very active as it did so with the peak rainfall on 15 June. Rainfall records were broken across the region,[11] leading to localised flooding. As it weakened, the front moved north into Scotland on 16 June and left England and Wales with a very unstable airmass, frequent heavy showers, thunderstorms and cloudy conditions. This led to localised flash flooding and prevented significant drying where earlier rains had fallen.

On 25 June another unseasonably low pressure (993 hPa / 29.3 inHg) depression moved across England. The associated front settled over Eastern England and dumped more than 3.9 inches (100 mm) of rain in places. The combination of high rainfall and high water levels from the earlier rainfall led to extensive flooding across many parts of England and Wales, with the Midlands, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, South, West and East Yorkshire the most affected. Gales along the east coast also caused storm damage. RAF Fylingdales on the North Yorkshire Moors reported rainfall totals of 4.1 inches (103 mm) in 24 hours, an estimated 3.9 inches (100 mm) in Hull and 3.0 inches (77 mm) on Emley Moor in West Yorkshire. Until 2007, the average monthly total for June for the whole UK was 2.86 inches (72.6 mm).[12]

On 27 June, the Met Office released an early warning of severe weather for the approaching weekend, stating that 0.79 to 1.97 inches (20 to 50 mm) of rain could fall in some areas, raising the possibility of more flooding within the already saturated flood plains.

On 20 July, another active frontal system moved across Southern England. Many places recorded a month’s rainfall or more in one day. The Met Office at RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire reported 4.98 inches (126.6 mm): a sixth of its annual rainfall. The college at Pershore in Worcestershire reported 5.60 inches (142.2 mm),[13] causing the Environment Agency to issue 16 further severe flood warnings.[14] By 21 July, many towns and villages were flooded, with Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Warwickshire, Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, London and South Wales facing the brunt of the heavy rainfall.

Climate researchers have suggested that the unusual weather leading to the floods may be linked to this year’s appearance of La Nina in the Pacific Ocean,[15] and the jet stream being further south than normal.[16]

Affected areas in England[edit]

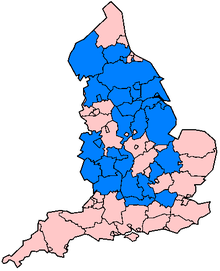

Non-administrative counties in England affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

Administrative counties in England affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

England was affected by the June and July floods, with the North badly hit in June, the West badly hit in July, and many areas hit in both. It was England’s wettest July on record.[17] Gloucestershire was the worst affected county – with both some minor flooding in June, and major flooding in July.[9] Non-administrative counties[18] and administrative counties[19] affected by the flooding are given below.

Bedfordshire[edit]

By 25 July, a number of low-lying parts adjacent to the river in Bedford and Luton were flooded[20][21] and one man drowned attempting to swim across the River Great Ouse in Bedford.[22] Parts of Felmersham[23] and Turvey[24] were also flooded.

Berkshire[edit]

Flooding outside Thatcham railway station on 20 July

On 20 July, the M4 was closed after a landslide caused by flooding between Junctions 12 and 13 eastbound.[25] Approximately 1,100 properties in Thatcham were affected by flash flooding.[26]

By 21 July, Newbury and Maidenhead town centres were flooded, the shopping mall in Maidenhead was closed and parts of the Glade Festival were flooded. Officials warned that the River Thames, the River Ock, and its tributaries from Charney could burst their banks.[27] Trinity School was badly affected by the flooding as well due to Vodafone’s HQ nearby. Vodafone’s ornamental lake overflowed due to the sudden downpour and badly damaged Trinity School’s astro turf to the front of the school as well as some damage to inside the school.

In Reading, rail services to the southwest were affected and westbound trains from Paddington could go no further.

The flood waters affected the Atomic Weapons Establishment at Burghfield, which handles Britain’s nuclear warheads, resulting in a suspension of work for almost a year.[28]

Buckinghamshire[edit]

On 3 June, Stoke Goldington suffered flash flooding affecting 25 homes.[29] Stoke Goldington was affected again on 3 July, with 10 houses being flooded.[30] By 21 July, seventy homes and businesses were flooded by the River Ouse in Buckingham and 30 people spent the night in the town’s Radcliffe centre,[27] but 10 miles (16 km) away a system of balancing lakes prevented Milton Keynes from suffering significantly, apart from a flash flood of Stony Stratford High Street from the River Ouse.[31][32]

Cambridgeshire[edit]

On 24 July, four bridges in St Neots, Cambridgeshire were shut when the river level peaked, and the Environment Agency warned residents in the St Neots, Paxton and Offords areas to expect flooding that night.[33] By 25 July, parts of St Ives were flooded.[34] Later the same day, the Environment Agency advised residents near the River Great Ouse that the peak had passed and further flooding was unlikely.[35]

County Durham[edit]

On 15 June, heavy rainfall caused the postponement of the fourth test match between England and the West Indies at the Riverside Ground, Chester-le-Street. On 23 June, flash floods affected parts of Darlington[36] and Stanhope Road, Northgate, St Cuthbert’s Way, Parkgate and Haughton Road were closed after water levels rose by about 2 feet (0.6 m). It has also led to Woodland Road to improve its drainage to prevent such flooding on one of the main roads out the town. On 17 July, flooding affected Peterlee town centre, closing shops and a local school.[37]

Cumbria[edit]

A 64-year-old man injured his head and died after trying to bail out his flooded home in Alston, Cumbria.[38]

A flooded Pizza Hut in Chesterfield

Derbyshire[edit]

On 25 June, flooding affected properties in Coal Aston, Calow and Chesterfield town centre, and the A617 was filled with more than 2 feet (0.6 m) of floodwater causing traffic delays.[39]

Gloucestershire[edit]

On 19 July, Gloucestershire Fire and Rescue Service attended 1,800 calls in a 48-hour period, compared with the usual 8,000 calls a year.[40]

On 22 July, Gloucester City A.F.C.‘s Stadium was flooded. Tewkesbury was completely cut off with no road access, parts of the town were under around 3 feet (0.9 m) of water and flood waters entered Tewkesbury Abbey for the first time in 247 years.[41] Tewkesbury’s Mythe Water Treatment Works were flooded.[9] Severn Trent Water warned that treated water would run out by early Sunday evening in Tewkesbury, Cheltenham and Gloucester.

Combined military and civil emergency services tried to stop floods reaching the Walham electricity substation in Gloucester supplying half a million people.[42][43] On 23 July 50,000 Gloucestershire homes were left without electricity after a major electricity substation in Castle Meads had to be turned off.[43][44] Efforts to stop flooding at Walham substation succeeded;[45][46] the Castle Meads substation was repaired the next day.[47][48][49][50] [51]

By 24 July, an estimated 420,000 people were without drinking water, including most of the population of Gloucester, Cheltenham, and Tewkesbury.[27] Emergency services continued repair work at the Mythe water-treatment works but Severn Trent Water estimated that water supplies would not be restored for at least 14 days.[47] 900 drinking water bowsers were brought in and the Army was mobilised to distribute three million bottles of water a day and keep the bowsers filled. Coors, Carlsberg, Scottish and Newcastle, Inbev and Greene King brewing companies offered 23 beer tankers to help supply drinking water. On 26 July Severn Trent Water organised a temporary non-potable water supply to 10,000 homes in Tewkesbury.[52] It was not until 7 August – 16 days after Mythe Treatment Works stopped pumping – that the tap water for the 140,000 homes affected was again declared safe to drink.[53]

In terms of casualties, a man and his 24-year-old son died from asphyxiation from carbon monoxide poisoning on 27 July when attempting to stop flooding in the unventilated Tewkesbury Rugby Football Club cellar.[54][55] On 28 July, the body of a 19-year-old boy, reported missing seven days earlier, was recovered in Tewkesbury.[56][57][58]

Greater London[edit]

On 20 July flooding occurred in many parts of Greater London. Water and power supplies were not disrupted but parts of South West London were under 2 feet (61 cm) of water. Heathrow Airport cancelled 141 flights. Two of four rail lines in South Croydon were closed by landslips.[4] The London Underground was severely disrupted and 25 stations were closed.

Herefordshire[edit]

By 19 June, Herefordshire was affected by flooding.[59] The M50 motorway near Ledbury was closed on 22 July due to flooding.[60] More than 5,200 people in and around Bromyard, Herefordshire were without clean water on 22 and 23 July after the pumps at the Whitbourne works in Herefordshire failed. Once supply was restored residents were urged by Welsh Water to boil their tap-water until further notice. The village of Hampton Bishop, 3 miles (5 km) from the city of Hereford remains surrounded and flooded by water after the River Lugg burst its banks. On the afternoon of 24 July the Fire Service began pumping flood water out of the village, but not before 130 residents were evacuated.[61] Houses, including the Herefordshire home of Daily Mail writer Quentin Letts, were flooded by a torrent of water gushing from what had previously been only a small, unnamed brook north of Ross-on-Wye.

Another incident in Bromyard, was when most of the residents of East Bromyard were rescued after the River Frome overflowed.

Lancashire[edit]

On 12 June, Lostock Hall and Penwortham near Preston were hit by flash floods.[62] On 3 July, heavy rain caused flooding in Earby[63] and Ribchester,[64] affecting homes and causing the Royal Lancashire Show to be cancelled on 9 July.[65] On 4 July, the Blackburn Mela was cancelled due to ground conditions.[66] On 18 July, Walton-le-Dale near Preston was hit by flash floods.[67]

Lincolnshire[edit]

On 25 June, the region was hit by flooding. Emergency services received more than 600 flood-related calls, roads were flooded in Grantham, Lincoln, Louth and Horncastle, homes in Louth and Langworth were flooded, the River Witham and Brayford Pool overtopped, people left their homes in Wainfleet, people were evacuated by boat from about 120 flats in Lincoln, and homes near Market Rasen and Scunthorpe, North Lincolnshire were left without power.[68] About 400 homes were evacuated in total.[68]

On 26 June, North East Lincolnshire was affected by flooding as about 50 Grimsby homes were evacuated by boat and the Army used to sandbag areas in Grimsby and Cleethorpes.[69]

Fields across the county were waterlogged, damaging crops and up to 40% of the pea harvest.[citation needed]

Although it did not formally flood, the Witham river came within inches of doing so. If it had, it would have created a 20-mile (32.2 km) wide lake, paralysing the county’s transport.

On 20 July, parts of Louth and Horncastle were hit by flooding again, and the main road in Covenham St Marys was under several feet of water.[70]

Nottinghamshire[edit]

On 27 June 2007, flash flooding caused extensive damage to the villages of Lambley, Woodborough and Burton Joyce. Major towns were hit including Mansfield and Hucknall but not as severely as Lambley. The same day, flooding occurred at Retford and Worksop after the River Idle and River Ryton respectively overtopped their banks.

Oxfordshire[edit]

Many rivers burst their banks, including both the Thames and the Cherwell in Oxford and the Ock in Abingdon and the Windrush and Evenlode in Witney.

By 21 July, Banbury[71] and Witney[72] were flooded. Oxford, particularly Botley, was flooded and some 300 people were evacuated.

On 22 July, the Environment Agency warned of further flooding and 1,500 people in Abingdon were evacuated. Forty thousand sandbags were transported from Grantham in Lincolnshire to Abingdon and Oxford.

By 23 July, Oxford, Abingdon, Kidlington and Bladon were affected; some 3,000 homes including the home of William Morris at Kelmscott were flooded and 600 residents were evacuated, with many taking refuge in Oxford United Football Club‘s Kassam Stadium.[73]

On 24 July the Thames in Abingdon rose 3 feet (0.9 m) in less than 12 hours to a “perilously high” level[46] and the Thames and the Severn were expected to rise to 20 feet (6.1 m) higher than normal.[43]

On 25 July residents of Osney in west Oxford were advised to leave their homes. About 30 people went to the Kassam stadium shelter while another 250 decided to stay with family and friends. Osney Mead substation, which supplies power to Oxford city centre, was threatened but did not flood. Later that evening, the Thames breached its banks at Henley.

Shropshire[edit]

Rising River Severn at Ironbridge, Shropshire, 28 June.

Bridge collapse in Ludlow, 26 June

By 19 June, rain had washed away the main road at Hampton Loade[59] and the Severn Valley Railway line from Bridgnorth was closed after numerous landslips on the line. Also, on 19 June/20 June, parts of the town of Shifnal near Telford, were flooded when the Wesley Brook burst its banks. Some of the residents blame Severn Trent Water for opening floodgates at Priors Lee balancing lake, however no such gates exist.[74] Repair costs to the railway were estimated at £2 million.[75]

On 26 June, the Burway Bridge collapsed, disrupting one of the main roads into Ludlow, severing a gas main and causing the surrounding area to be evacuated.

On 1 July, a woman was pulled out of the River Severn at Jackfield on the Telford and Wrekin border near Ironbridge.[76] By 24 July, the UK National Ballooning Championships in Ludlow had been cancelled for the first time in their 32-year history.[77]

Warwickshire[edit]

By 21 July, flooded parts of Warwickshire included Alcester, Stratford-upon-Avon, Shipston on Stour and Water Orton. To a lesser extent, areas of Leamington Spa and Warwick also experienced flooding.[78]

Several nature reserves in the Tame Valley, including Ladywalk and Kingsbury Water Park were badly affected, just as ground- and reedbed- nesting birds were hatching young.[79]

West Midlands[edit]

200 people were forced to leave Witton Road and Tame Road in Aston, Birmingham when the River Tame flooded. Water entered the streets of Shirley, Solihull.[27] As in Warwickshire, the Tame caused losses at a nature reserve; this time RSPB Sandwell Valley.[80]

Wiltshire[edit]

On 20 July, Swindon had a month’s rainfall in less than half a day. More than 50 people were rescued from their flooded homes.[81]

Worcestershire[edit]

By 19 June, Worcestershire was affected by flooding.[59] A 68-year-old motorist died after he was trapped in his vehicle in flood water near Pershore whilst attempting to cross an old ford in Bow Brook which was by then 2 m deep.[82][83] The waters were still rising, endangering the confluence of the River Teme and the River Severn. On 26 June 2007 the New Road Ground, home to Worcestershire County Cricket Club, was flooded after the River Severn overtopped its banks, causing the next day’s Twenty20 match against Warwickshire to be cancelled.[84] On 17 July, Tenbury Wells in Worcestershire was flooded for the second time in three weeks after a thunderstorm caused flash flooding.[85] By 21 July the M5 was affected, compounded by the closure of the Strensham services, and the motorway was closed, stranding hundreds in their vehicles overnight.[86]

By 23 July, parts of Worcestershire were under 6 feet (2 m) of water and the Army was brought in to help emergency services supply the inhabitants of Upton-upon-Severn which was cut off by floodwater.[27]

On 1 June, the first day of the floods. A road in Cropthorne near Worcester was brutally forced down by a high impact of water flowing underneath the road in a pipe. The hole it made was 13 feet (4.0 m) deep and 33 feet (10 m) wide, traffic throughout the county was held up due to the collapsed main road. The site was named Cropthorne Canyon.

East Riding of Yorkshire and Kingston upon Hull[edit]

On 15 June, the region was hit by flooding. Roads including the A63 and A1105 in Hull and schools in the region were closed, the Hull Lord Mayor’s Parade was cancelled, the Festival of Football was postponed, police declared a major incident and Hessle in Hull, on the border between one council and the other, suffered two square miles of severe sewage-contaminated flooding.[87]

On 25 June, the region was hit by flooding again. Fire crews received over 1500 calls in a 12-hour period,[88] dozens of homes in Beverley and about 50 people at a Hull nursing home were evacuated,[69] boats were used to evacuate about 90 people from 4 feet (1 m) of floodwater in Hull’s County Road North,[69] and in Hessle a 28-year-old man died after becoming trapped in a drain.[89] The new Hull police station had to be vacated because of flooding. The next day, only 12 of Hull’s 88 schools were still open, affecting 30,000 out of 38,000 Hull schoolchildren.[90]

By 4 July in Hull, six schools were still closed and 120 residents in residential or nursing care had been relocated.[91]

By 5 July, an estimated 35,000 people[92] in streets containing 17,000 homes[91] had been affected by flooding in Hull and by the next day more than 10,000 homes had been evacuated.[93] Hull City Council estimated repair costs at £200 million.[92]

By 24 July, Hull City Council had checked each house in the flooded streets and stated that 6,500 homes had been flooded.[94]

By 27 July, £2.1 million had been allocated to Hull and £600,000 to the East Riding for clean-up and immediate repairs,[95] and £3.2 million to Hull and £1.5 million to the East Riding for further repairs to the region’s estimated 101 schools suffering significant flood damage.[96]

By 3 September, figures released by Hull City Council had been revised upwards to 7,800 houses that had been flooded plus 1,300 businesses that were affected.

North Yorkshire[edit]

By 15 June, towns and villages in North Yorkshire were flooded, with Knaresborough, Harrogate and York being particularly affected.[97] In Scarborough, the main A171 Scalby Road flooded outside Scarborough Hospital, and the ornamental lake at Peasholm Park overtopped its banks and poured down Peasholm Gap into North Bay. Near Catterick, North Yorkshire, a 17-year-old soldier on a training exercise from Catterick Garrison died after being swept away whilst crossing Risedale Beck, Hipswell Moor.[98] On 23 June, flooding affected Middlesbrough.[36] Pickering was flooded after Pickering Beck overflowed its banks. On 18 July, streams overflowed and roads were blocked in Barton, Gilling West, Melsonby, Hartforth, Scotch Corner, Middleton Tyas and Kirby Hill after a freak rainstorm,[99] and on 18 July 2007 a cloud burst left parts of Filey under 3 feet (1 m) of water, just caused by the rain, rather than by a river bursting its banks. Pensioners were stranded in the town’s swimming pool and rescued by lifeboat.[100]

South Yorkshire[edit]

A road near Meadowhall Centre showing extensive flooding after the River Don burst its banks

On 25 June, Sheffield suffered extensive damage as the River Don over topped its banks causing widespread flooding in the Don Valley area of the city. A 13-year-old boy was swept away by the swollen River Sheaf,[101] a 68-year-old man died after attempting to cross a flooded road in Sheffield city centre,[102] and several cattle were washed away, found up to 3.5 miles (5.6 km) across fields in some areas of cultivated land. The Meadowhall shopping centre was closed due to flooding with some shops remaining closed downstairs until late September and Sheffield Wednesday’s ground Hillsborough was under 6 feet (1.83 m) of water. A number of people were rescued by RAF helicopters from buildings in the Brightside area,[103] whilst in the Millhouses Park area to the southwest of the city the River Sheaf overtopped its banks causing widespread damage.[104] There was also widespread flooding in Barnsley, Doncaster and Rotherham with much of these towns cut off.

By 26 June, the waters in some parts of Sheffield and the surrounding area receded, and over 700 villagers from Catcliffe, near Rotherham‘s Ulley reservoir were evacuated after cracks appeared in the dam.[83][105] Emergency services from across England pumped millions of gallons of water from the reservoir to ease the pressure on the damaged dam, and the nearby M1 Motorway was closed between junctions 32 and 36 as a precaution.[106]

On 27 June, the Army moved into the Doncaster area after the River Don overtopped its banks and threatened the area around what was Thorpe Marsh Power Station. A man was incorrectly reported missing near the village of Adwick le Street near Doncaster.[107]

The river in Clayton West just after the flooding

West Yorkshire[edit]

On 15 June and on 25 June, the villages of Scissett and Clayton West and other parts of Kirklees were flooded by the River Dearne, the second time worse than the first.

On 29 June, Wakefield was flooded. Six elderly women, including a 91-year-old, were stranded in their homes.[108]

During the Wakefield flood, hundreds of homes were evacuated in the Agbrigg area of Wakefield and looting was feared, but by 1 July only four looters had been arrested in the city and were later released on bail.[109]

The Leeds village of Collingham (near Wetherby) was particularly affected by the flooding and one house was looted.

Affected areas in Northern Ireland[edit]

Non-administrative counties in Northern Ireland affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

Districts in Northern Ireland affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

Northern Ireland was hit by flooding in the June and July floods and it was Northern Ireland’s wettest June since 1958.[110] The non-administrative counties[111] and districts[112] affected are given below.

County Antrim[edit]

On 12 June, the Knockmore campus of the Lisburn Institute in Lisburn was affected by flooding. The same day, parts of East Belfast near the Antrim-Down border that were affected included the Kings Road, Ladas Drive, Strandtown Primary School and the Parliament Buildings in Stormont, with 80 residents evacuated from their old people’s home on the Kings Road and Avoniel Leisure Centre opened to assist flood victims.[113][114] On 2 July, houses were flooded and two people evacuated from their home in Cushendall in Antrim after the River Dall burst its banks following heavy rain.[115][116] On 16 July, parts of Belfast International Airport near Aldergrove in Antrim were flooded by a freak thunderstorm leaving 10 planes unable to land,[117] landslides closed the Antrim Coast Road near Ballygally, Larne, and people were trapped in their cars in Portrush, Coleraine.[118][119]

County Down[edit]

On 15 June, there was severe flooding around Bangor in North Down, Saintfield, Crossgar and Ballynahinch in Down and Newtownards and Comber in Ards, with shops in Crossgar centre flooded.[120]

County Londonderry[edit]

On 12 June, Magherafelt was affected by flooding.[113][114] On 16 July, roads in Aghadowey, Coleraine[118][119] and Portstewart, Coleraine[117] were rendered impassable by floodwater.

County Tyrone[edit]

On 12 June, Omagh and Dungannon were affected by flooding, with a Dunnes supermarket evacuated in Omagh.[113][114]

Affected areas in Scotland[edit]

Lieutenancy areas of Scotland affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

Council areas in Scotland affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

Scotland was hit by flooding in June and July, with the Scottish Lowlands most badly affected. On 12 June, the Met Office issued torrential rain warnings for Scotland[121] and it was Scotland’s wettest June since 1938.[122] The non-administrative counties[18] and council areas[123] affected are given below.

Ayrshire and Arran[edit]

On 21 June, about 2000 homes were left without electricity and properties were affected as flash floods hit Kilmarnock.[124] On 18 July, flooding affected Kilmarnock again, the River Irvine burst its banks in Newmilns, and flash floods affected roads including the M77.[125]

Dumfries[edit]

On 18 July, floods wrecked homes in Closeburn, power was cut off at Eaglesfield, and roads were closed at Moffat and Lochmaben.[126]

Edinburgh and Midlothian[edit]

On 1 July rain cancelled the one-day international cricket match between Scotland and Pakistan in Edinburgh[127] and by 3 July parts of Midlothian were flooded, with worst hit areas including residential areas in Dalkeith and Mayfield.[128]

Glasgow and Lanarkshire[edit]

On 22 June, heavy storms flooded roads[129] and dumped debris on the railway line in Glasgow.[130] The same day, torrential rain caused a landslide just south of Lesmahagow, closing the M74.[131]

Moray[edit]

On 3 July a landslide caused by floodwater disrupted traffic on the A941 Rothes to Aberlour road in Moray.[132]

Ross and Cromarty[edit]

On 18 July, heavy rain caused landslips blocking the railway line between Strathcarron and Achnasheen for a predicted 10 days,[133]

Tweeddale[edit]

On 25 June rain forced the 108-year-old Beltane Festival in Peebles to be held indoors for the first time.[134]

Affected areas in Wales[edit]

Non-administrative counties in Wales affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

Principal areas in Wales affected in June and July 2007 floods as of 24 July (marked in blue).

Wales was hit by flooding in June and July, with the Eastern areas most badly affected. It was Wales’s wettest June since 1998, and its second wettest since 1914.[135] The preserved counties[136] and principal areas[137] affected are given below.

Clwyd[edit]

On 26 June, roads including the A5 were impassable at Corwen in Denbighshire, a river overflowed at Worthenbury in Flintshire, and properties were affected in Wrexham.[138] In North Wales, a man was rescued by fire services after he was stranded on a small island in the River Dee in Llangollen, Denbighshire. On 17 July, flash floods after torrential rain forced the closure of a secondary school in Prestatyn in Denbighshire.[139]

Dyfed[edit]

Lampeter in Ceredigion was affected by flooding on 11 June[140] and then again on 15 June.[141]

Gwent[edit]

On 26 June, properties were affected in Tintern on the River Wye in Monmouthshire.[138] On 20 July, flash floods affected parts of Newport, Monmouthshire and Torfaen.[142]

Powys[edit]

In Montgomeryshire, ten people were taken to safety at Tregynon and a dozen homes were flooded at Bettws Cedewain on 22 July,[143] firefighters used a boat to evacuate five people from a house near Welshpool after they were cut off by floods on 23 July,[144] and the same boat was later used to rescue three people stranded in a car on the A483.[143] In Radnorshire, 30 tonnes of debris and earth blocked the only road out of Barland near Presteigne on 23 July.[144] In Brecknockshire, the River Wye burst its banks in Builth Wells on 1 July,[145][146] the saturated ground later causing chaos at the Royal Welsh Show in Llanelwedd on 24 July.[147]

South Glamorgan[edit]

On 20 July, flash floods affected the Vale of Glamorgan,[148] causing schools to be evacuated, roads to be closed, and boats used to rescue people from their homes in Barry.

Timeline for June and July floods[edit]

Areas affected by flooding during this period were as follows (see above for specific citations):

- 1–7 June:

- England (Buckinghamshire)

- 8–14 June:

- England (Lancashire),

- Northern Ireland (Belfast, Cookstown, Dungannon, Lisburn, Magherafelt, Omagh),

- Wales (Ceredigion)

- 15–21 June:

- England (County Durham, Herefordshire, North and West Yorkshire, Shropshire, Worcestershire),

- Northern Ireland (Ards, Down, North Down),

- Scotland (Ayrshire, Lanarkshire),

- Wales (Ceredigion)

- 22–28 June:

- England (East Riding of Yorkshire, Hull, Nottinghamshire, Shropshire, Worcestershire, South Yorkshire),

- Scotland (Peebles),

- Wales (Denbighshire, Flintshire, Monmouthshire, Wrexham)

- 29 June – 5 July:

- England (Buckinghamshire, Lancashire, West Yorkshire),

- Northern Ireland (Antrim),

- Scotland (Midlothian, Moray)

- 6–12 July:

- De facto gap between the June and July floods

- 13–19 July:

- England (County Durham, Cumbria, Lancashire, North Yorkshire, Worcestershire),

- Northern Ireland (Coleraine, Larne),

- Scotland (Ayrshire, Dumfriesshire, Ross and Cromarty),

- Wales (Denbighshire)

- 20–26 July:

- England (Bedfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Gloucestershire, Greater London, Herefordshire, Lincolnshire, Oxfordshire, Warwickshire, Wiltshire, Worcestershire),

- Wales (Newport, Monmouthshire, Powys, Torfaen, Vale of Glamorgan)

Aftermath[edit]

Rescue effort[edit]

Following the flooding in late June, the rescue effort was described by the Fire Brigades Union as the “biggest in peacetime Britain”.[5] Following the flooding in July, the RAF said it is carrying out its biggest ever peacetime rescue operation, with six Sea King helicopters from as far afield as RAF St Mawgan in Cornwall, RAF Valley in Anglesey and RAF Leconfield in the East Riding of Yorkshire rescuing up to 120 people.[6][7][8][9][149] An RAF heavy lift Chinook helicopter was also employed to move aggregate to reinforce the banks of the River Don.[150] The Environment Agency described the situation as “critical”.[9]

4×4 Response groups from throughout the UK assisted councils and blue light services during and in the immediate aftermath of the flooding. During the recovery phase a number of responders from around the UK 4×4 Response assisted the Red Cross in the distribution of fresh drinking water in the Gloucestershire area after mains drinking water was contaminated.

Health risks[edit]

The Health Protection Agency advised people that the risk of contracting any illness was low but that it was best to avoid coming into direct contact with flood water. There were no reported cases of any outbreaks. In some areas bottled water was handed out where sewage works got flooded.

Crop damage[edit]

The floods caused widespread crop damage, especially broccoli, carrots, peas and potatoes. In parts of Lincolnshire it was estimated that 40% of the pea crop may have been damaged, with other crops also suffering major losses. Prices of vegetables were expected to rise in the following months.[151]

Financial cost[edit]

Environment Agency chief executive Baroness Young said that about £1 billion a year was needed to improve flood defences. The Association of British Insurers has estimated the total bill for the June and July floods as £3 billion.

A report by the Environment Agency in 2010 concluded that “the scale and seriousness of the summer 2007 floods were sufficient to classify them as a national disaster”, and that the “total economic costs of the summer 2007 floods are estimated at about £3.2 billion in 2007 prices, within a possible range of between £2.5 billion and £3.8 billion.

Government response[edit]

On 3 July, Environment Secretary Hilary Benn announced that the Government would increase the spending on risk management and flood defences by £200 million to £800 million by 2010–11.[152] During Prime Minister’s Questions in the House of Commons later that month, Prime Minister Gordon Brown promised £46 million in aid to flood-hit councils and £800 million rise in annual spending on flood protection by 2010–11, confirming Hilary Benn’s announcement. Brown also pledged to push insurance firms to make payouts.

On 22 July, the Government convened COBRA to co-ordinate the response to the crisis.[153]

Visiting Gloucestershire on 25 July, Mr. Brown praised emergency services for their efforts, but added: “We’ve got to get the supplies stepped up. We will get more tankers in, we will get more bowsers in, we will get more regular filling of them, and at the same time, more bottled water will be provided.”[52]

On 8 August 2007 Defra announced that Sir Michael Pitt would chair an independent review of the response to the flooding. On 4 September of that year the Cabinet Office website launched a comments page to let people affected by the flooding contribute their experiences to the review.

Sir Michael published his interim report on 17 December 2007.[154]

In April 2010 the government passed the Flood and Water Management Act 2010, which implemented many of Sir Michael Pitt’s recommendations.[155] The Act gives more power and responsibility to the Environment Agency and local authorities to plan flood defences co-ordinated across catchment areas and the wider country, to counteract the tendency for defences to be built for upstream areas without much thought for how this might be making flooding worse for downstream areas. In also brings in a new regime whereby new building activity which exacerbates flooding by reducing the capacity of land to absorb water will need to be accompanied by the construction of sustainable drainage systems such as grassy roofs, ponds and soakaways.

Criticism of Hull Council[edit]

Hull Council was criticised for not insuring the city’s libraries, schools and other public buildings. In response, Hull Council said that “Many councils do not have the feature in their budget”,[citation needed] but other flood-hit councils were insured. It was thought that council tax payers would be left with the bill, as emergency Government funding would not cover it.

Criticism of government response[edit]

Jenna Meredith, one of the victims of flooding, was one of the most high profile critics of the government response.[156]

In June, councillors in Hull claimed that the city was being forgotten and had the floods occurred in the Home Counties, help would have arrived much more quickly. One in five homes in Hull was damaged and 90 out of the city’s 105 schools suffered some damage. Damage to the schools alone was estimated to cost £100 million. The Bellwin scheme for providing aid after natural disasters was criticised as inadequate by Hull MP Diana Johnson.[157] The lack of media coverage of flooding in Kingston upon Hull led the city council leader Carl Minns to dub Hull “the forgotten city”.

In July, the Government came under mounting criticism of its handling of the crisis, the fact that responsibilities were spread across four departments and no single minister could be held responsible, and the fact that the Army had not been called in to assist.[158]

The Observer newspaper stated on 22 July 2007 that the Government had been warned in the spring by the Met Office that summer flooding would be likely because the El Niño phenomenon had weakened, but no action was taken.[159]

In response to the criticism, Environment Secretary Hilary Benn said on BBC Sunday AM that “This was very, very intense rainfall, with five inches in 24 hours in some areas; even some of the best defences are going to be overwhelmed”. He praised the way the emergency services had dealt with “unprecedented” levels of rainfall and said he had “total confidence” in the response of the Environment Agency.

Conservative leader David Cameron called for a public inquiry into the flooding after visiting Witney, the main town in his Oxfordshire constituency.[160]

Then Liberal Democrat leader Sir Menzies Campbell accused the government of lack of preparation leading to a “summer of suffering”, and said, “With sophisticated weather forecasting as we now have, particularly in relation to what’s happened over the weekend, there are quite a few questions as to how it was that flood-prevention measures were not in place or were not more effective.”

FEATURE IMAGE CREDIT: Daily Mail

Recent Comments